Chicago’s Hispanic Murals: The Walls that Talk

Historic Chicago muralists keep this public art form alive as new artists emerge with visions and techniques that aren’t necessarily the same as the most traditional methods. Experts and artists agree on one thing: it’s important to preserve existing murals and create new ones

Roberto Valadez’s mural on 26th and Pulaski streets in La Villita. (Antonio Zavala / La Raza) Crédito: Impremedia

For Carlos Tortolero, president of the National Museum of Mexican Art, there is no need to group Hispanic artists in an organization since they communicate with one another and organize their art exhibitions through social networking.

“There is no need to direct them; they are very intelligent,” said Tortolero, the 1987 founder of this iconic museum in Chicago.

Under the Yollocalli Arts Reach program, created in 1997, this museum has been able to teach young people how to create murals. To date, this program has completed nearly 50 murals, including three inside the Rauner YMCA building in Pilsen.

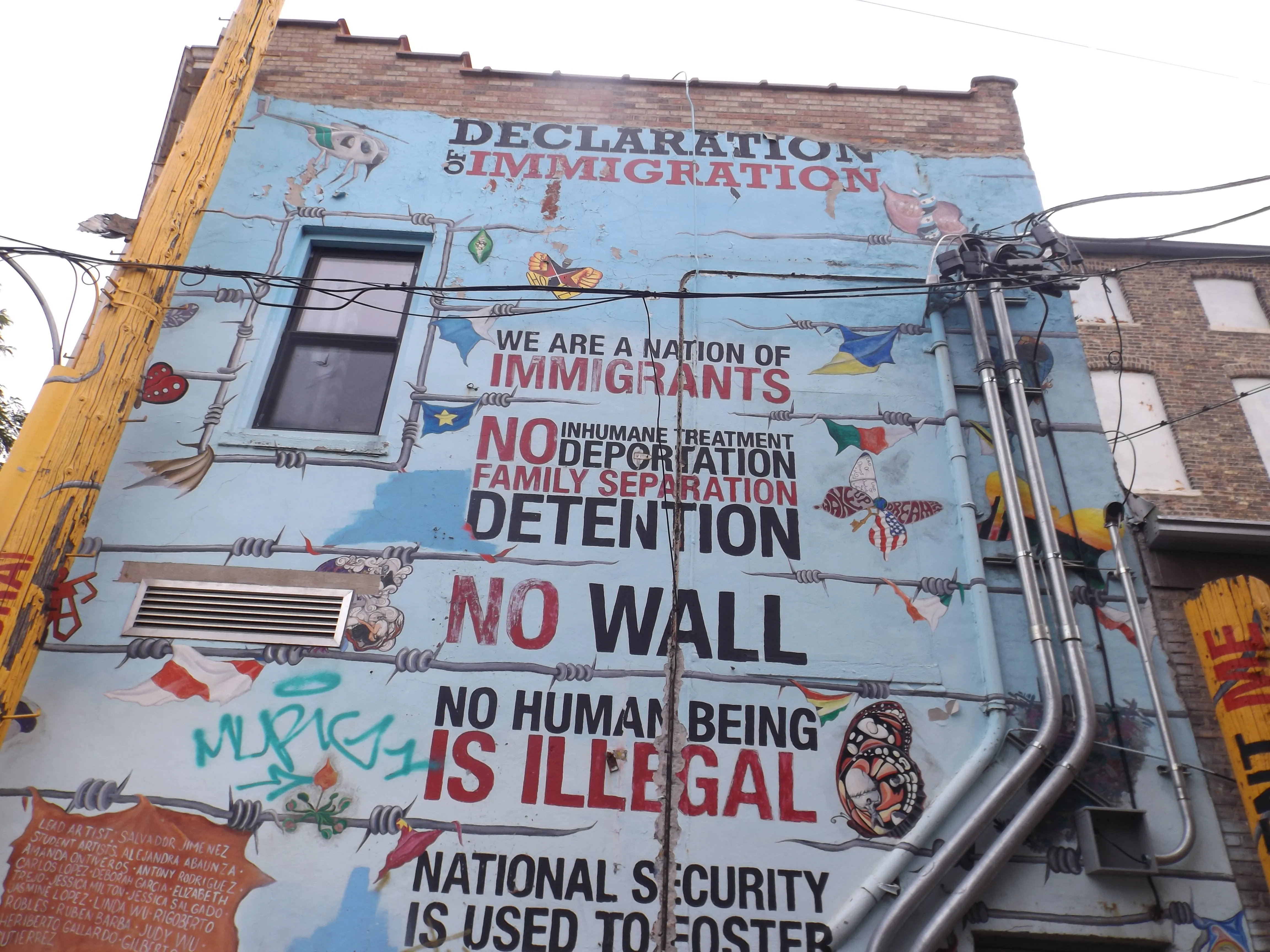

One of the most iconic murals in Pilsen is the one created by the youth of the Yollocalli program in 2016 near 18th Street and Blue Island Avenue. The two-story-high mural is titled ‘Immigration Declaration,’ which, among other messaging, proclaims that “no human being is illegal.”

The program’s mural was recently unveiled in the Little Village Public Library on 23rd Street and Kedzie Avenue in the Little Village neighborhood.

The museum, Tortolero noted, also acts as a resource center and connects public schools seeking to create a mural inside their campuses with the artists.

“From our beginning, we have always been involved with the artists, and we did not charge a fee; many times, the professional compensations are for the artists,” said Tortolero.

“Murals are very fashionable, and in Pilsen, murals are everywhere,” said Tortolero.

Although there is no exact count of murals in Hispanic neighborhoods, the City’s Register of Murals lists 356 artworks, including murals in Spanish-speaking neighborhoods and the rest of the city.

Marcos Raya

Perhaps the staunchest critic of the trend to create murals with graffiti techniques and capture images that have already been repeated in many places in the neighborhood is the muralist painter Marcos Raya, a native of Irapuato, Guanajuato, Mexico, who moved to Chicago in 1964.

After studying art in Massachusetts, Raya returned to Chicago and worked at Casa Aztlan as an artist in residence and dedicated himself to offering art workshops to young people in the community.

Raya amazed the neighborhood and the world of art in 1972 when he painted his mural ‘Homenaje a Diego Rivera’ or ‘Tribute to Diego Rivera’ (a famous Mexican artist) located next to a hardware store on the corner of May and 18th streets.

Another of Raya’s outstanding murals is the one he painted at the corner of 18th Street and Western Avenue titled ‘No More Dictatorships.’ The mural displays a crowd demolishing the statue of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza.

But Raya, already nationally recognized, is putting up a battle against what the artist calls “taco art,” which he describes as the Mexican cultural clichés already overused countless times on the neighborhood walls.

These images, Raya pointed out, don’t contribute to art nor send a political message to communities that continue to experience social problems.

“Instead of taking art seriously, they spend time copying, designing the same images, and this is a very simple and clumsy way of making art,” the artist said.

Raya even believes that all young people of Mexican origin have lost their identity. That’s a fear that afflicts him.

“The advice I can give them, what I can tell them, is that painting murals is part of a real movement, a social movement,” said Raya. “Muralism is to educate.”

“I don’t understand graffiti; it doesn’t tell you anything,” said the muralist. “It can even be reactionary so that painting is not sending a message.”

Roberto Ferreyra

Roberto Ferreyra is recognized in Pilsen for his work with Aztec dance and the Son Monarcas music group music, but he is also known for his art.

Ferreyra, a native of Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico, painted a giant mural in 2019 dedicated to the case of the 43 Ayotzinapa students who disappeared in Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico, six years ago.

The mural ‘The Night of Iguala’ is in Western Avenue and 18th Street in the Pilsen neighborhood.

That 275-feet long by 16-feet high mural is in itself a cry of protest and a call not to forget this horrific case that shocked Mexico and the world.

Ferreyra acknowledges that the type of muralism that began in the city’s Hispanic neighborhoods in the past no longer exists.

“What we see on the walls now is something else; it is not the muralism we knew 30 years ago,” said Ferreyra.

Decades ago, the walls of neighborhoods like Pilsen were immersed in images created by muralists such as Mario Castillo, Ray Patlan, Salvador Vega, and Marcos Raya.

According to this artist, new generations of young people have brought another style to the walls of the neighborhoods.

“Graffiti has invaded with huge insignificant images,” said Ferreyra, who was brought to the city in 1993 by the National Endowment for the Arts, and after finding a vibrant Mexican population in Chicago, he decided to stay.

Ferreyra, 63, said that the new generations must learn more about the trends of Mexican muralism and the concept of public art.

“I believe that artists are not up to the task of what is happening; the muralists from before had a relevance with what was happening,” the artist said.

Sandra Antongiorgi

The muralist painter Sandra Antongiorgi was born in Utuado, Puerto Rico, but her parents decided to move to the Chicago Pilsen neighborhood at an early age.

“We were a Puerto Rican family living in a Mexican neighborhood,” she recalls.

The family later moved to Humboldt Park but eventually moved to Little Village on the city’s southwest side.

Antongiorgi notes that she has been a muralist painter for three decades and has always been fascinated by the power of art to influence people.

“One of the reasons I dedicated myself to art is that I saw the power it has to speak to a large number of people,” she said. “Art also ignites conversations, and we hope it inspires social change.”

Antongiorgi, in cooperation with artist Sam Kirk, created the mural ‘Weaving Cultures’ in the vicinity of 16th Street and Blue Island Avenue in Pilsen in 2016. The 15-foot tall by 40-foot wide mural pays tribute to marginalized women who haven’t been recognized by society.

Antongiorgi launched a campaign in 2018 for the City of Chicago to create a mural registry after a crew from the Department of Streets and Sanitation removed her ‘It’s Time to Remember’ mural, which was on Pulaski Street and Avenue Bloomingdale in Humboldt Park.

The mural honored the culture, music, and art of Puerto Rico. One day, the mural was gone without warning.

After that experience, the City created the Chicago Register of Murals, which, as previously mentioned, has 356 registered murals.

“We have to unite, and we have to protect these places; sometimes these are masterpieces,” Antongiorgi said.

As a woman, Antongiorgi takes on the challenges of finding the spaces to paint murals and “represent the Puerto Rican people as much as possible.”

“Back in the days when I started painting, work was always given to men. I can’t let that happen to the next generation of female artists,” she said.

Roberto Valadez

Roberto Valadez doesn’t mind in the least that young people today use other techniques to capture their murals outdoors.

“There are a lot of young people creating new spontaneous jobs like the ones we saw in plywood in looted shops [businesses covered their windows and doors with wooden plywood to protect their buildings from the looting in the city in mid-2020],” Valadez said. “I like the spontaneous nature of these works, although sometimes they are a bit chaotic.”

Valadez, 57, began his career in art when he was young and helped other muralists create works of public art inside the walls of Benito Juarez High School.

“I started painting with the Casa Aztlan summer program,” said Valadez, who is about to begin the renovation of the image of the Aztec sun and the Coyolxauhqui moon on the platform of the CTA train at the 18 Street station. The late Francisco Mendoza created those images, and Valadez has been commissioned by the City to renew them.

Valadez points out that today there is more willingness by merchants to allow artists to capture art, including murals, on their buildings’ facades.

“More artists are creating murals today, although it can be said that many times they are basic images, a visual language is being created,” Valadez said. “My opinion is that the more competition, the better.”

Perhaps Valadez’s most notorious masterpiece is the mural next to a bank near the 26th and Pulaski streets in Little Village. This beautiful mural, full of rich imagination, contains images of civil rights activist César Chavez, historical Mexican figures Miguel Hidalgo and Emiliano Zapata, community activist Rudy Lozano, and Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, among others.

This mural was originally painted by the late artist Vicente Mendoza in the 1980s. Valadez, sponsored by Second Federal Savings bank, repainted it but in his own style in 2016.

Milton Coronado

The life of artist Milton Coronado has been like a roller-coaster ride.

At the age of 5, he lost his mother, Ema Coronado Diaz. Later his father, Ramiro Coronado, married two more times, which caused Milton to misbehave. He even belonged to a gang, and today he admits that he vandalized properties with graffiti when he was young.

Later, his father, Ramiro, was assassinated in September 2001. After some soul searching, Milton turned his life around. He studied at the American Academy of Art, where he graduated in arts and design and learned painting and illustration techniques.

Coronado, 40, is now skilled using watercolor, acrylic, spray and oil painting, and other styles.

A mural that he created in honor and memory of his father led him to think collectively and inspire hope, not grievance, to others.

Today, Milton is the renowned muralist who painted in 2018 a touching mural in memory of Marlen Ochoa, the pregnant mother who was brutally murdered and whose baby was torn from her womb.

Coronado has created other murals honoring the murdered Army soldier Vanessa Guillen, hip-hop artist Chance the Rapper, Mexican boxer Canelo Alvarez, essential workers, and many more.

Although he began with the tradition of graffiti, this artist indicated that he knows Mexican muralism.

Through art, Coronado, whose family came from Guadalajara, Mexico, tries to alleviate the pain caused by social problems in the neighborhoods.

“The arts such as music, literature and everything that has to do with art foment our spiritual growth,” the muralist reflected.

Hector Duarte

Hector Duarte arrived in Chicago in 1985 from Zamora, Michoacán, Mexico, with a muralism background, which he learned from workshops by the well-known muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, one of Mexico’s three greatest muralists.

Duarte, 68, has painted about 50 murals in Chicago and elsewhere, including several in Mexico.

His house in Pilsen, located near the National Museum of Mexican Art, attracts visitors as it’s decorated with the mural ‘Oliver in Wonderland,’ which intertwines on the house’s exterior.

Duarte says he admires today’s young muralists who use the aerosol-can technique to create new murals.

“I don’t see it as a negative thing,” Duarte said. “With the spray cans, they make an image in an instant.”

“There are some young people who are very good at painting; they have mastered the spray-can technique and have reached realism,” Duarte added.

However, this muralist recommends that young people read and study history “to find out what happened before.”

This, he said, is to prevent young people from falling into pamphleteering that “after two or three months [the art] no longer has value.”

Muralists, Duarte warned, must also consider the culture of the different neighborhoods to transmit their solidarity to those communities.

What used to take months, artists can do a mural in a few days thanks to the new methods, which facilitates the creation of public art.

Duarte likes to paint his murals in bright colors that resemble the sun. “I attribute this to my Latin American origins,” he said.

This artist has also created mobile murals, and one of them was exhibited at the Cervantino Festival in Guanajuato, Mexico.

Victor A. Sorell, art historian

For art historian Victor A. Sorell, distinguished professor emeritus at Chicago State University, murals in the city play an important role.

“They are a testament to the reality that social events, political events, inform art and, in turn, art informs the society in which we live,” said Professor Sorell.

The recent Black Lives Matter protests, he says, are creating a lot of murals. Sorell, a native of Mexico City, noted that in the ’60s and ’70s, the city had perhaps 40 or so Latino muralists who were very influential.

“I think now, in the last few years, there has been a fusion between graffiti art and murals or graffiti writing and murals,” Sorell said.

Among his many achievements, Sorell edited the book on the life of the late local artist Carlos Cortez titled ‘Carlos Cortez Koyokuikatl: Soapbox Artist & Poet.’

On whether he thinks that the memory of the three great muralists of Mexico —Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros— is no longer so fresh in the minds of the new generation of Hispanic muralists, the distinguished professor said: “Yes, I think the influence of the Big Three has overshadowed some efforts, but I think the ideology behind the murals of Mexico, especially the ideology of Siqueiros, has still informed some of the Latinx muralists in Chicago and elsewhere. But as we move into the 21st Century, I think that legacy is not so evident in the murals we see now.”

What are the fundamentals of muralism? The large size, location, and message, he said.

“The murals have to be big and be on your face. What makes them unique in America, not just Chicago is that they are street art. I guess that message is everything for murals. The murals speak directly to people; it’s like Marshall McLuhan said: the medium is the message,” Sorell said.

—

The production and dissemination of this story has been possible thanks to a grant from the Field Foundation of Illinois through its Media and Storytelling program. La Raza appreciates its support.