“We teach them not only how to change their neighborhoods but also how to change their lives”: Berto Aguayo

The organization Increase the Peace focuses on pulling young people away from gangs, offering them educational and future job opportunities, and reducing violence in neighborhoods such as Back of the Yards, Little Village, Pilsen, Gage Park, and Brighton Park, among others. Its founder, Berto Aguayo, managed to escape from a gang, is about to graduate as a lawyer from Northwestern University, and was a fellow at the Chicago Community Trust

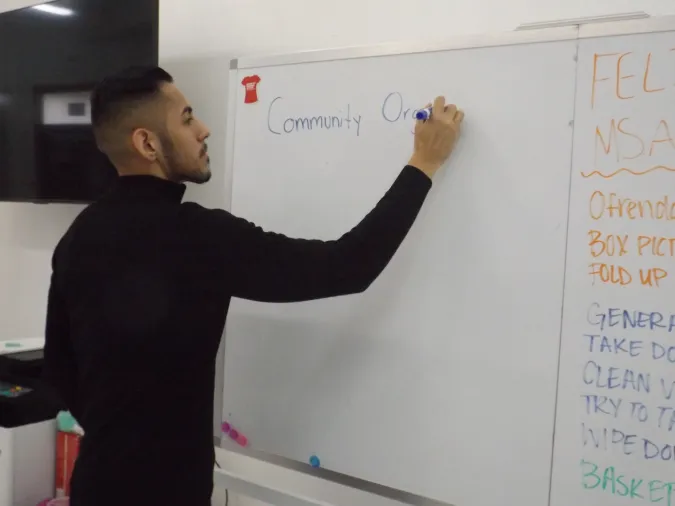

Berto Aguayo, founder of Increase the Peace, an organization dedicated to reducing violence in Chicago neighborhoods and offering young people educational and job opportunities. (Antonio Zavala / La Raza) Crédito: Impremedia

Your zip code should not determine your future or the opportunities you should or can have in life.

This is how Berto Aguayo, a community leader from Back of the Yards and founder of the Increase the Peace organization, whose mission is to provide leadership, guidance, and training to young people to steer them away from violence and towards seeking opportunities and careers they can pursue in life, expresses himself.

Aguayo emphasized, in an interview with La Raza, that if you are a Hispanic youth between the ages of 16 and 24, you are more likely to fall into the clutches of violence if you do not have a clear path to a better future.

In many cases, Hispanic and minority youths between these ages are neither employed nor attending any school that prepares them to learn a trade, a career to equip them with skills so that they themselves, as adults, can start their own business.

“I escaped from a gang”

Berto Aguayo, 29, was a typical youth from our community: he wanted to learn and be something in life, but along the way, he encountered several challenges. One of them was growing up without the presence of his father in his life.

Like many Hispanics in the city, Aguayo’s parents immigrated from Mexico, specifically from Jalpa, Zacatecas.

In 1994, Aguayo’s parents arrived as immigrants in Chicago and went to live in Back of the Yards. That’s where Aguayo was raised as part of a family of five brothers and three sisters.

Aguayo says that as a child, he attended James Hedges Fine Arts School, on 48th and Winchester streets.

“There, I had good and bad experiences,” Aguayo recounted in an interview. “There, they supported me so I could learn English, which was something new for me.”

Aguayo recounted that he was in the fifth grade and about 11 years old when he finally learned to speak English.

But a few years earlier, when he was still in the second grade, an Anglo-Saxon teacher asked him a series of questions. Since he could not answer, as he did not yet know English, the teacher removed his chair and desk for several days, something Aguayo felt was “very humiliating in front of the other children.”

After the incident, Aguayo did not want to return to school until his mother, Rosalba Contreras, a professional stylist, went to the Hedges school for a meeting with the principal, and they managed to get the Anglo-Saxon teacher to apologize.

Even so, the dangers of the street haunted this leader who today seeks to guide young people towards a better future.

At 13, perhaps due to a lack of guidance or good examples, Aguayo joined a street gang. At that time, he was attending Acero-Major Hector P. García Middle School in the Archer Heights neighborhood in Chicago.

Because of his involvement with the gang, his behavior and grades were failing. Aguayo faced a possible suspension from middle school until the principal advised him to find a job and leave the gang.

“I don’t want something to happen to you during this summer,” the principal told him.

Aguayo decided to leave the gang at 17, when he was about to finish high school. As a rite of passage, he recounted that the gang members “gave me a brutal beating lasting three minutes during which the gang members kicked me, hit me, and yelled insults at me.” But in the end, Aguayo noted, “I felt free and saved myself.”

Under intense pressure, Aguayo found a job in the offices of then alderwoman Michelle Smith, in the 43rd District, which includes the affluent Lincoln Park neighborhood on the city’s north side.

It was during that summer that Aguayo learned to perform various jobs in that community, and his perspective, he said, took a 180-degree turn.

“That summer, I was exposed to the inequality we live in,” said Aguayo. “And by that time, I was still a gang member, and no one spoke well of me.”

Aguayo said that during that summer, he noticed all the services available in Lincoln Park that his own community did not have, “but it was a transformative opportunity for me.”

Slides of violence

In Hispanic neighborhoods like Little Village, Pilsen, Brighton Park, and Back of the Yards, among the most violent in Chicago, most victims of violence are under 25 years old.

And in Chicago, a city of 2.7 million residents, violence in certain areas of the city has inhabitants on edge.

Crimes recorded in the city include armed carjackings, assaults with firearms on pedestrians, mass or group robberies of all types of establishments, waves of thefts from street food vendors, and, perhaps most devastating and painful for the population, the indiscriminate use of firearms to attack others.

To understand the violence in the city of Chicago, a radiography, or in this case, a slide of those that were projected on a screen in classrooms, is sufficient.

As of November 19, 2023, a day like many others, this is the toll of violence due to firearms and the ease of obtaining and using them on the streets of Chicago: 326 people shot, according to statistics from the Chicago Police Department. Of that number, 46 people died from gunshot wounds. The other 280 people suffered various degrees of injuries, were transported to hospitals, and were able to survive and continue with their lives.

Let’s see another slide of violence in the streets, parks, and more spaces of the big city.

On November 27, 2023, 14 armed robberies were reported, according to the police, across Chicago. It was theorized that a group of four men between the ages of 18 and 25, dressed in dark clothing and driving an Audi A5 car, robbed that number of people in the neighborhoods of Little Italy, Pilsen, Brighton Park, Back of the Yards, and others.

Four of the victims were beaten to take their belongings. In each case, the thieves took cell phones, wallets, and other valuables from the victims.

Also police violence

Compounding the situation are cases of police members who shoot people, mostly people of color, in various scenarios.

One such case was that of teenager Adam Toledo, who was shot to death by a white police officer in Little Village on March 29, 2021.

As has been narrated in the media, Toledo, just 13 years old, was running through an alley in Little Village at 2:38 am and, when he reached an opening in a wooden fence, threw what was possibly a gun to the ground and immediately raised his hands. That’s when Officer Eric Stillman of the Chicago Police Department, who was chasing him, shot him dead.

The death of Toledo, one of the youngest victims of these aggressive police acts, sparked protests in the city and other parts of the country.

Even more well-known than the Toledo case is that of 17-year-old African American Laquan McDonald, who was hit by 16 bullets fired by police officer Jason Van Dyke on October 20, 2014, in the Brighton Park neighborhood.

Before the available videos of the incident were shown, it was said that McDonald had acted erratically and was carrying a bladed weapon in his hand. When made public, the videos showed that the young man was walking away from the scene and turning his back to the police when Van Dyke opened fire. Then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel asked then-Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy to resign.

The ramifications of this incident were greater than those of the Toledo case. Van Dyke received six years in prison for second-degree murder and aggravated assault.

A new direction

After graduating from high school in 2012, Berto Aguayo took an important new step in his life and enrolled at Dominican University in River Forest, Illinois. There, he graduated in economics and political science in 2016.

“Everything I hadn’t done in high school, I achieved in college,” Aguayo specified. “I had the purpose of arming myself with an education, and I graduated with honors and high grades.”

After his bachelor’s degree, Aguayo has now spent three years studying at the Northwestern University School of Law. His graduation is projected for May 2024.

“I have a goal, and perhaps that’s why I’ve changed,” he pointed out in an interview. “I work now so that other young people don’t have to go through what I went through.”

Aguayo told La Raza that he decided to create the Increase the Peace organization to replicate opportunities for young people and to get them out of gangs.

“My mission is to be able to help these young people,” Aguayo said during an interview.

Looking back, Aguayo says that it was the death of a young Hispanic woman in Back of the Yards in 2016 that gave him the motivation to establish this new organization.

The young Naome Zuber was traveling in a car headed to a birthday party with three friends on October 1, 2016, when someone shot from the sidewalk, hitting Zuber, just 17 years old, in the head. The incident, one of many in the city, occurred at 12:30 am on the 4500 block of S. Wood Street.

As a result of the incident, about 200 Hispanic youths gathered at 48th and Wolcott streets and camped out overnight as a form of vigil and remembrance for the young victim, who was in her last year of high school at Curie and wanted to study criminal justice in the future at a university.

“A new movement was born that night,” Aguayo explained to La Raza.

“The impulse to establish our organization was the tragedy of that girl,” Aguayo emphasized.

Then, in 2021, amid the rage and anger over the death of Adam Toledo, Aguayo recalled, his organization staged a protest march in Little Village.

Significant achievements

Seven years after its founding, Increase the Peace has trained more than 300 young people in civic organization techniques in their communities, according to the group’s website.

Although based in Back of the Yards, a neighborhood full of history and near to the former slaughterhouses called Union Stockyards, closed in 1971, the youths helped by this original organization and community center also come from other neighborhoods like Pilsen, Little Village, Brighton Park, Gage Park, and West Lawn.

Another skill or ability taught to young people, mostly Hispanics and equally children of immigrants who left their towns and cities in Mexico and other Latin American countries to come live and work in Chicago, is how to become leaders and how to seek and fight for social change.

“We teach them not only how to change their neighborhoods but also how to change their lives,” Aguayo indicated.

The vital work of the Increase the Peace organization includes forming peace circles among young people and communities, and actions to resolve conflicts, restore justice, and expose young people to different opportunities and careers.

Under this latter purpose, Aguayo specified that he and his small team of volunteers take Hispanic youths to other communities and institutions so they can learn about new opportunities and see that it is possible to have a future.

For example, Aguayo frequently takes groups of young people to the Northwestern University School of Law in Chicago and to the University of Illinois Veterinary College in Urbana Champaign, two and a half hours south of the city.

Aguayo indicated that it is of vital importance to expose our young people to academic careers and other trades for which young people can aspire and improve their lives.

Fresh in the mind of this leader representing a new generation is the fact that he did not know there was a better world out there, far from the invisible barriers and poverty of disadvantaged neighborhoods. In his particular case, it was only when he went to work in Lincoln Park, a high-income neighborhood with a majority of white residents, that he realized he could change his life and transform it by studying something of interest to him, in this case, the profession of lawyer that he will practice in the near future.

“Your zip code where you live should not limit you,” said Aguayo about inequality in the city.

Indeed, another service that Increase the Peace provides to Hispanic youths is free legal advice in case they have a problem with the law. It is offered every Monday from 3 pm to 8 pm at the Increase the Peace office (1900 W. 48th Street, Chicago), thanks to the Beyond Legal Aid firm.

And if that were not enough, this new organization also offers mentorship to young people, giving each young person access to people who have developed a career or profession so that the young person can ask questions and learn from the model’s or professional’s experiences.

Jorge Agustín, a 26-year-old young man, joined Increase the Peace almost at the same time as the organization was founded.

“Increase the Peace was a space for me and for many young people in the community,” Agustín specified. “The organization gave us a sense of belonging and empowered us to make social changes in the community.”

Agustín, of Mexican parents, said he is about to take the law school admission test, known as the LSAT in English, because he now also wants to study law and be a lawyer who can make a difference in his community.

“Aguayo’s group gave us a lot of motivation and helped us chart a plan for our lives,” concluded this young Hispanic.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Increase the Peace also offered workshops on public health and during the sanitary confinement stage of 2020, young people helped deliver food to street food vendors who were impacted by the lack of customers during that period.

To conclude, Increase the Peace, according to Aguayo, also promotes peace between the African American and Latino communities and seeks a link and understanding between them.

For this purpose, Aguayo recounted, an annual car parade is organized in Marquette Park between both communities.

Aguayo considered that misunderstandings and distancing between different communities are what sometimes cause mistrust and even unleash outbreaks of violence. “It’s a blessing to be able to do this work,” Aguayo concluded. “And to be able to say: I can be the person I needed when I was young and be happy with that person.”

Contact Increase the Peace

Address: 1900 W. 48th Street, Chicago, IL 60609

Email: increasethepeacechi@gmail.com, info@increasethepeacechicago.org

Website: www.increasethepeacechicago.org

Facebook page: www.facebook.com/increasethepeacechicago

—

The production and publication of this La Raza report have been made possible in part thanks to the support of the Chicago Community Trust through its Cross Community Impact program.