Enlace Chicago: Social Fighters Preventing Violence and Opening Opportunities for Social Reintegration

Enlace Chicago works to prevent violence in the streets of Little Village, offering opportunities for youth to channel their future and for individuals who have completed their sentences to reintegrate with dignity into the community

Jason Maldonado, coordinator of the Illinois Latino Reintegration Community Collaborative at Enlace Chicago. (Courtesy of Jason Maldonado) Crédito: Cortesía

Enlace Chicago is a community organization with a 34-year legacy of existence and community struggle for the benefit of over 100,000 residents who live, work, and attend schools in the Little Village area. This organization began in 1990 as the Little Village Community Development Organization. In 1998, it opened its first office in the area and hired its first employees. During this time, the organization focused on creating a comprehensive community development plan.

In 2008, the organization changed its name to Enlace Chicago and diversified its community development and activism plan. The organization now operates from its headquarters at 2759 S. Harding Avenue in the Hispanic neighborhood of Little Village. This neighborhood, located about 6 miles southwest of downtown Chicago, is one of the most economically dynamic communities in Chicago, with a sales tax contribution to the city only surpassed by the affluent Michigan Avenue. However, apart from the challenges of seeking employment and finding high-performing schools, this area, ranging from Cermak Street to 31st Street and from Kostner Avenue to Western Avenue, is also a hotspot for street gang activity that, over the years, has left a long list of young victims.

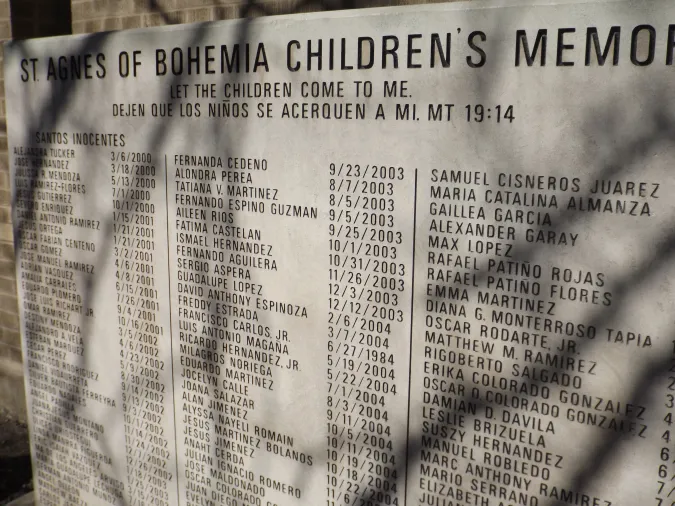

In a dramatic and equally painful act, the Catholic Church St. Agnes in Little Village once displayed the names of victims of street violence outside its walls. It was a distressing task for many neighbors to read the names of the young fallen in the streets at such a young and tender age.

After its reorganization in 2008, Enlace Chicago has participated in establishing eight community networks that connect Little Village with similar efforts in other communities across the metropolis.

Through its participation with city networks seeking to improve the quality of life, especially in areas combating high poverty and high violence, Enlace Chicago developed initiatives in four main areas: education, public or community health, immigration, and violence prevention. Enlace Chicago estimates that since 2008, the staff of this organization – which includes professionals, paraprofessionals, health and education counselors, and several street outreach workers – has served a total of 8,000 young people between the ages of 13 and 21 and also a large number of adults.

Violence Prevention

On the topic of violence prevention in high-poverty areas in Chicago, where a significant portion of the city’s Hispanic population lives, Enlace Chicago programs, one of the largest organizations in Little Village and the city, focus on attending to violence victims with counseling and mental health services, and in counseling in public and some private schools, where the largest number of Hispanic youth, mostly of Mexican descent and in many cases US-born Hispanics of Mexican immigrant parents, are found. Since 2005, Enlace Chicago became the lead agency to implement the CeaseFire program, which focused on preventing violence among youth in various communities.

To launch this program in Little Village, the organization stated that “Enlace takes a comprehensive, multisystemic, trauma-informed approach to build safety and peace in Little Village.” Under CeaseFire, Enlace Chicago highlighted the use of a number of “comprehensive strategies to mitigate and prevent conflict between groups and individuals.” In addition, Enlace Chicago states that it “organizes activities throughout each year that promote peace.” Moreover, Enlace Chicago operates a program for the reintegration into society of citizens returning from state prisons. In this context, the word “citizens” is used to refer to all former prisoners who, for one reason or another, committed a crime, were arrested, and sentenced to serve time in an Illinois prison after facing a criminal trial in the courts.

Street Outreach Workers

Guillermo Gutiérrez is the coordinator of the Street Outreach Workers that Enlace Chicago sends to the streets of Little Village to talk to youth to address or mitigate an act of violence that has already occurred or perhaps to prevent and stop a violent act that is about to happen. Gutiérrez, 50, highlighted to La Raza that in Little Village operate members of three street gangs and therefore, for work purposes, the organization Enlace Chicago has divided Little Village into three zones to which this organization sends, or has working, several street outreach workers.

Street outreach workers know the youth in each zone, talk to them, invite them to different recreational events, maybe even an outdoor barbecue. On other occasions, street outreach workers even organize outdoor parties to which they invite the youth and also adult neighbors of the area. In certain zones or safe havens, street outreach workers also invite youth to participate in video games, watch movies, or sometimes even play cards. Through these conversations and various events, street outreach workers get to know the youth and, over time, guide them towards finding alternative paths for their lives, possibly even returning to high school and eventually enrolling in a university. “I’ve seen many young people take a new turn in their lives,” says Gutiérrez, of Mexican origin.

One of the most important factors in assisting youth is being able to engage in conversation with them and understand what they are going through, Gutiérrez pointed out. Gutiérrez shares that he grew up in Little Village in the 1960s and knows the community well. He is also aware of the risks that young people can face. “Violence can affect anyone at any time,” says Gutiérrez. “Little Village has a lot of violence.”

Gutiérrez mentions that when he was young, he always thought he wouldn’t live past 17 years old. “I’ve been shot, stabbed, and I’ve been to jail after a violent incident,” Gutiérrez recounts about his youth in Little Village. He now oversees six street outreach workers, two counselors, and one person who advocates for victims of violence.

Gutiérrez stated that what he looks for in a street outreach worker is someone who can navigate or move through the three zones of Little Village that Enlace Chicago has demarcated for the purposes of its vital work. “Street outreach workers must have a certain level of respect from the youth and inspire trust in them,” explained Gutiérrez.

Despite the challenging terrain that must be navigated in Little Village for young people, Gutiérrez affirms that he has seen many success stories among them. “I’ve seen how street outreach workers meet with the youth, talk, communicate, and many young people have been convinced that they don’t have to belong to any group,” concluded Gutiérrez.

Guillermo Niño: A Successful Outreach Worker

Guillermo Niño is the lead outreach worker at Enlace Chicago and one of the most successful outreach workers in the organization dedicated to mitigating and trying to end violence. As Guillermo Gutiérrez told La Raza, “violence is a complex issue. It affects many people, both the perpetrator and the victim, as well as relatives and friends on both sides.”

Regarding this, Niño, 49, mentioned that he has seen with his own eyes the success that can come from positively intervening in the lives of young Latinos and Mexicans in Little Village, an area shared by three gang groups operating in this large and successful community in the southwest of the city of Chicago. Niño explained that he has been the lead outreach worker at Enlace Chicago for almost four years but has already seen the fruit of his work and that of the organization. “Five of the young people I’ve talked to and lived with are now in university, another ten have found work and have been working full-time for the last two and a half years,” emphasized Niño, also of Mexican origin.

Niño focuses his intervention in the area from California Avenue to Damen Avenue and from Blue Island Avenue to 18th Street, an area that covers the west of Pilsen and the east of Little Village. “If young people need any assistance, I’m always there,” said this outreach worker.

Niño stated that he is proud that in the area where he intervenes, there have been no incidents of violence in the last two years. “Not even a shooting or even a broken bottle,” Niño assured in the interview conducted with him by La Raza at the beginning of 2024.

Niño also gives credit for the help received in these peacekeeping efforts to the administrators of the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) housing complex and Ofelia Santiago, the director of the city park near 24th Street and Washtenaw Avenue.

Jacqueline Herrera, Director of Violence Prevention

Jacqueline Herrera, a social worker by profession and who until January 2024 was the director of the Violence Prevention Program at Enlace Chicago, mentioned that the organization uses a holistic model to provide a series of services to the youth of Little Village. Among these services is providing counseling inside and outside public schools by outreach workers who seek to eradicate the remnants of violence in the victims.

Herrera, 33, mentioned that almost all of Enlace Chicago’s clients receiving violence-related services are born and raised in Little Village. The four schools that have an agreement with Enlace Chicago to provide counseling to the youth are Community Links High School, Eli Whitney Elementary School, Farragut Community Academy, and Madero Middle School.

Herrera, who worked at Enlace Chicago for about 7 years, indicated that the organization’s workers provide support services not only to the young victims of violence but also to the entire family. “Violence not only impacts the victim but also the father, the mother, and the uncles of the victim,” specified Herrera, who left Enlace Chicago a few days after the interview.

Providing Safe Havens for Youth

In interviews with outreach workers from Enlace Chicago, several of them mentioned the importance of providing safe havens to the youth of Little Village. Enlace Chicago’s outreach workers typically have a safe haven in each of the three zones into which this organization divides Little Village. In these safe havens, young people can listen to music, chat with outreach workers, play games, and often hold outdoor parties where adult neighbors are also invited to get to know the youth and see them beyond the label of “gang members.” All interviewees indicated that interaction and communication between outreach workers and youth are key to guiding young people towards a fruitful future, including entering a community college or university and changing their lives.

At Enlace Chicago, outreach workers usually refer young people, depending on their particular case, to a case manager who reviews and analyzes the intervention needs of the case. Then, they review the specific needs for counseling, physical health, and mental health to provide these services to the youth. Herrera noted that depending on the program, Enlace Chicago serves about 65 youth at a time. In recent years, it has provided services to more than 100 youth and their families, Herrera mentioned.

Herrera emphasized again that through community events organized by Enlace Chicago throughout the year, more youth are informed about the organization’s services. These events include block parties, outdoor barbecues, and activities during holidays such as Labor Day at the beginning of each September, which is, disturbingly frequently, the most violent weekend in the city of Chicago. Herrera added that it usually takes from 7 months to a full year to assist a victim of violence.

Starting Again in Little Village

Enlace Chicago is also part of the Illinois Latino Reintegration Community Collaborative, a program to assist people, referred to as “citizens,” in reversing the negative perception that follows ex-prisoners returning to the community after serving their sentences. Max Cerda is the regional coordinator of this initiative aimed at helping returning citizens reintegrate into society, their communities, and families.

This collaborative involves 80 organizations across the city, and each participating community organization, Enlace Chicago among them, is assigned 10 cases of citizens for reintegration into society. Cerda, 62 years old, explained that Enlace Chicago works with the Puerto Rican Cultural Center in the city on this task. “It’s very frustrating,” Cerda said, “Nobody wants to employ a citizen returning from jail to the point where we ask ourselves, how long does their punishment last?”

Cerda mentioned that returning citizens continue to be stigmatized, but it is necessary to find them employment that they can perform. Not only that, but many of the family members have also changed, as have the returning citizens themselves. Many are no longer the same. “It’s a long process to help returning citizens feel comfortable in their skin,” added Cerda. “It’s difficult.”

Cerda mentioned that sometimes, by returning to their own culture, Hispanic citizens returning from prison manage to feel well and heal. “Culture heals,” Cerda noted, saying this includes books, music, dance, and other cultural activities like theater.

Cerda shared that he went through many things in his youth in Chicago. “I was lost when I was young,” Cerda recounted. “My brother died in my arms, I was 18 years old, I wanted to heal, I wanted my culture, my identity, I wanted to have hope, energy.”

“In the end,” Cerda specified, “we are as effective as the young people are receptive.”

Jason Maldonado: People Do Change

Another leader in the Illinois Latino Reintegration Community Collaborative is Jason Maldonado, who has worked for Enlace Chicago since October 2020. He himself, he said, is a citizen who returned to the community after serving a sentence in jail. Maldonado, 56, believes that Latino citizens returning from prisons lack services to help them reintegrate back into society. Often, Maldonado said, Latinos must seek these services in African American communities, where they encounter language and sometimes cultural issues.

“Why do Hispanics from our community have to go outside to receive these services? We should be capable of offering these services to our returning citizens,” Maldonado pointed out. Among the many services often required by Latinos just released from jail are mental health therapy, anger management, and assistance in combating alcoholism. Additionally, returning citizens require a place to live, an identification card, a driver’s license, clothes, and a job, Maldonado emphasized.

Other vital services include expunging their criminal records when they have been found innocent and seeking tattoo removal from their bodies. Under this initiative at Enlace Chicago, a tattoo expert removes tattoos from hands, neck, or body for $20, when elsewhere this can cost up to $200.

And finally, Enlace Chicago has a program in coordination with Metropolitan Family Services that provides legal aid, particularly for expunging an arrest or incarceration record after the person was found innocent.

“Keep in mind that these young people are not angels, but people do change. I believe everyone deserves a second chance to contribute to society,” Maldonado said. Maldonado affirmed that many of the citizens returning from prisons possess intelligence and talent.

Both Max Cerda and Jason Maldonado emphasized that for people who have been in prison, the punishment continues outside in society. “If you have a conviction in court, your punishment continues outside in real life,” Maldonado pointed out. And Cerda added, “many returning citizens are stigmatized to the point where we ask ourselves, when does their punishment end?”

Safe Passage and Schools

In addition to its work with youth, Enlace Chicago also coordinates the efforts of the Safe Passage Program, which employs individuals to ensure safe routes to school and back home for students from 14 schools in Little Village and Pilsen. The program creates a safety environment with adults patrolling the routes to schools with two-way radios to prevent violence. Enlace Chicago collaborates with administrators and staff of each school, the Chicago Police Department, and parent and neighbor organizations to establish a safety habitat.

The schools with which Enlace Chicago coordinates these efforts are Benito Juárez Community Academy, Charles G. Hammond School, Community Links High School, Eli Whitney Elementary School, Farragut Community Academy, Irma C. Ruiz School, John Spry Elementary School, Joseph E. Gary Elementary School, Lázaro Cárdenas Elementary School, Little Village Lawndale High School, María Saucedo Academy, Pickard Elementary School, Telpochcalli Elementary School, and William E. Finkl Academy.

Epilogue: A Violent Incident

Just as the writing of this report was being concluded, a violent shooting was reported in Little Village in the early hours of Sunday, February 11, 2024. The incident was reported on the 3500 block of W 30th Street, near St. Louis Avenue, and it was said that five people were injured, one of them a woman with serious injuries. The incident apparently broke out after an argument between a man around 53 years old and a young person, who began to shoot a weapon. The injured woman was taken to a hospital, apparently with several bullet wounds to her body. The aggressor, it was reported, fled in a vehicle. Another story that, dramatically, shows that to prevent and face violence, every effort is key, and there is much to be done.

Contact Enlace Chicago

Address: 2759 S. Harding Ave. Chicago, IL 60623

Email: info@enlacechicago.org

Website: www.enlacechicago.org

Facebook page: www.facebook.com/enlacechicago

Phone: 773-943-7570

—

The production and publication of this story by La Raza have been made possible in part thanks to a grant from the Chicago Community Trust through its Cross Community Impact grant program.