The grim reality of wage theft: Cook County workers continue to be misled

Workers in Cook County lose about $9 million a week in wage theft, according to experts. Immigrant workers tend to be the hardest hit as many work in industries that pay minimum wage, are unaware of their employment rights, and often don’t seek help for fear of retaliation

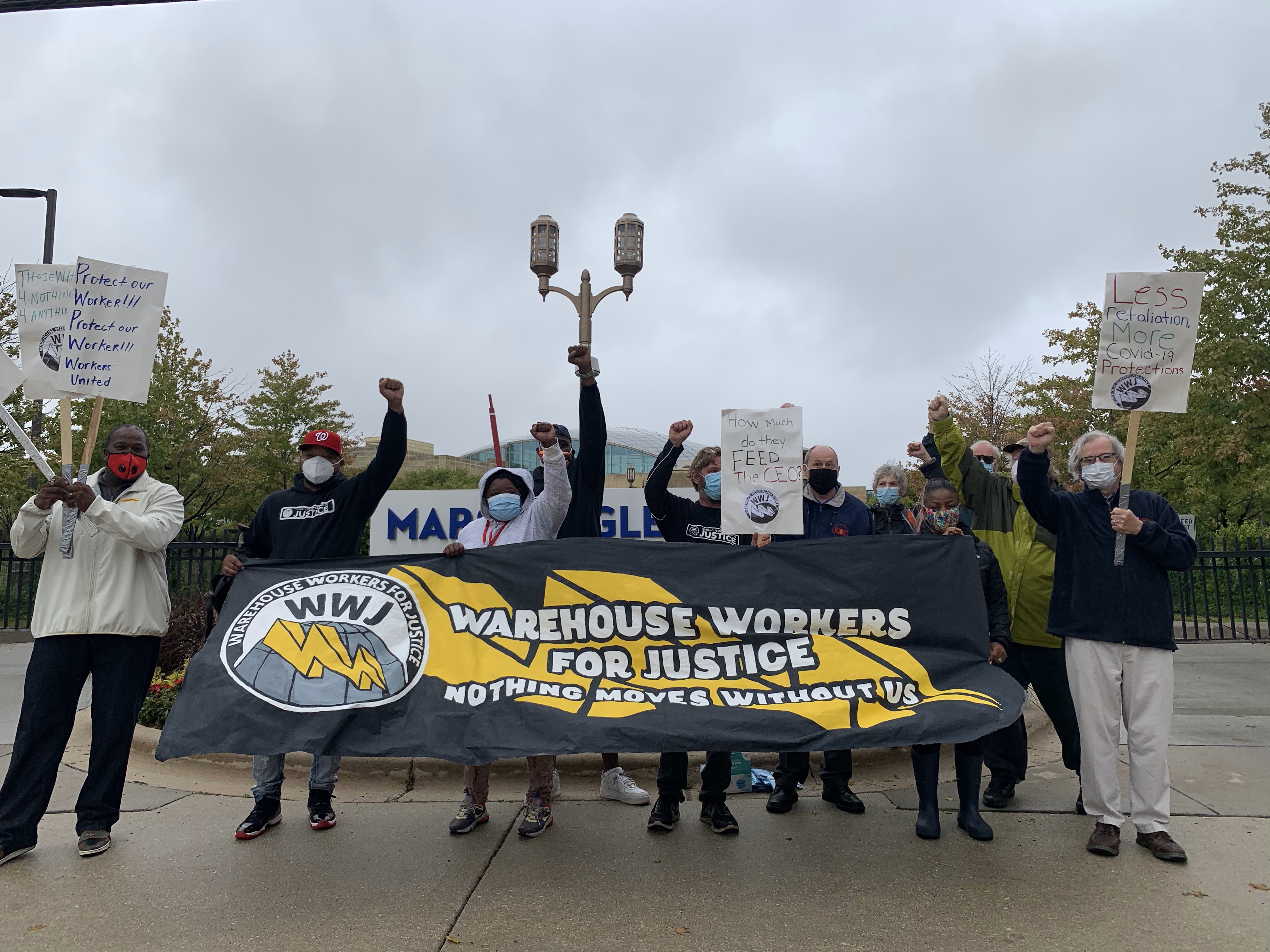

Chicago Community and Worker’s Rights recovered more than $1.5 million in 2019 for workers. (Courtesy of Chicago Community and Workers’ Rights) Crédito: Cortesía

CHICAGO – Nicolas Fuentes will never forget the day when he showed up to work at Olmarc Packaging Co. in North Lake. Unexpectedly, he and his wife, Isabel, who also worked there, and hundreds of other workers, were notified that the plant was shutting down and that their services were no longer needed.

Fuentes, a workers’ union leader employed at Olmarc Packaging since 1990, along with the rest of the workers, were left in utter shock. It was the beginning of a long journey to recover what the company owed to the Fuentes couple, around $1,014 each, for unused vacation and a full week’s salary.

After three years of a legal battle that began with a complaint to the Illinois Department of Labor and that ended up in the hands of the state prosecutor’s office, it was determined that the Fuentes and at least 500 workers would not recover a single dollar of the wages owed to them because the company had declared bankruptcy.

“Look, the labor center [Labor Department] doesn’t help the poor. They only help companies and the rich. There was nothing we could do,” Fuentes said. “Most of the workers had worked at the company between 15 to 20 years. Many trusted the owner’s word. And many trusted me. Many people hoped that I would continue fighting. When we found out, they were disappointed in me and everyone. We were done,” Fuentes said with immense frustration as if the event had happened yesterday.

When Olmarc Packaging closed in 2008, the company had facilities in North Lake and Franklin Park. It employed about 2,000 workers, according to Martin Unzueta, executive director of Chicago Community and Workers’ Rights.

“This company got used to telling workers to accumulate vacation time, assuring them that if the vacation time was not used it would be transferred to the following year. So it was like a normal practice to accumulate vacation. There were workers who had been accumulating vacation for up to three to four years,” Unzueta said.

Many suspect, among them Unzueta and Fuentes, that the company’s owners, the brothers Aldo, Dennis and Ken Marchetti, opened another factory under another name and in another location, making millions in profits. The company sold its assets through an online auction at BIDITUP on October 28 and 29 of 2008.

But this assumption has been difficult to confirm. According to Dona Leonard, an official with the Illinois Secretary of State, the agency cannot “determine what business this employer would have opened under a new name. We’d need the name of the business in order to search our records.”

Nicolas Fuentes, 79, and his wife Isabel, 67, were never able to find another job. He believes that job opportunities were denied to both of them due to their ages. Although they appreciate their children’s economic and moral support, the memory of what happened to them brings them sorrow and disappointment due to the injustice inflicted upon them and hundreds of workers.

Workers lose approximately $9 million a week

A massive 2008 study on wage theft, carried out collaboratively by a group of researchers, organizations and universities, including the Center for Urban Development at the University of Illinois at Chicago, found that workers in Cook County lose around $7.3 million per week in owed wages. Considering the country’s economic inflation, that figure today would be equivalent to about $9 million, according to Alison Dickson, an instructor with the labor education program of the School of Labor and Employment Relations at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Dickson, who participated in the research, said the amount was calculated based on thousands of surveys to workers in industries that pay minimum wage.

“This study had such a ripple effect because the findings were so damning. [For example] Hilda Solis was the Secretary of Labor at the time under President Obama. Immediately after reading that report she hired 1,000 more inspectors for the U.S. Department of Labor. You know, those are the kind of impacts we want to have,” Dickson said.

Chicago elected officials also took notice, generating several ordinances to support workers, including the Sick Leave Ordinance, which came into effect in 2017, and the Fair Workweek Ordinance, which took effect in July 2020, to regulate workers’ hours.

The irregularity of work schedules, according to Dickson, “is something that is especially seen in the retail trade and food service, where workers really cannot count on how many hours they are going to work per week.”

Despite the measures, the problem of wage theft in the country has not improved but has worsened, according to Dickson and other professionals dedicated to battling this stark problem, which disproportionately affects immigrant and undocumented workers.

“The minimum wage has gone up. So there are employers who are finding new ways to try to think of a way to cheat and basically to minimize their losses or make profits on the backs of poor workers,” Dickson said. “I’m seeing a lot more people who are facing things like working off the clock or working on what’s known as ‘close openings,’ when you close, then you end the shift at the end of the night, but then you have to open first thing in the morning.”

With COVID-19, wage theft is ‘worse than ever’

Have wage thefts worsened during the pandemic? “It is worse than ever. We have seen many irregularities,” said Jorge Mujica, labor campaigns organizer for Arise Chicago. Before the pandemic, Arise received 30 to 40 calls a week from workers who needed help. From April 2020 to today, Mujica said they receive 80 to 100 calls a day with wage-theft complaints.

As minimum wages increased as of July 2020 —$13.50 per hour in Chicago for employers with four to 20 workers, and $14 per hour for employers with 21 or more workers— Mujica said his organization has seen many cases where employers are telling their workers they cannot give them pay raises because of the crisis. Therefore, many are cutting wages illegally.

Mujica added that it has been difficult to confirm whether these companies have received government help through the Payroll Protection Program (PPP), a federal aid measure for small businesses that have been affected by the coronavirus crisis.

“The aid was not exclusively to pay salaries, so there is no obligation,” Mujica said. “In restaurants, for example, the bosses have told the workers that ‘well there is no money, so I’m just not going to pay you.’ [Restaurants] have always been a big problem.”

Martin Unzueta, who also serves as board vice president for Raise the Floor Alliance, said that the most critical cases are seen among workers in hotels, restaurants, and construction in Chicago, but more directly in downtown. “We have received a lot of complaints from people who have to work from 3 in the afternoon until midnight, and then they open at 7 in the morning, for example. That is a violation of the law,” Unzueta said.

The Chicago Fair Workweek Ordinance dictates that every worker must be notified of schedule changes seven days in advance. The measure was designed for companies to establish stable work schedules.

According to Unzueta, another issue that is happening more frequently is the “open-and-close” tactic to pay workers less. “Unfortunately, the law allows them. Many places say ‘well we don’t need so many people anymore so we are going to close.’ Then, they close the business and within a week they reopen and hire new people with lower salaries. Unfortunately, that’s not against the law because companies can hire and fire whoever they want as long as those workers are not under a collective contract,” Unzueta said.

A worker of Mexican descent, Elizabeth Perez, was one of those affected. It began when she started working at Capri Lounge & Grill restaurant in Willow Springs in February of this year to wash dishes and help in the kitchen. The chain restaurant is owned by 5 Brothers Inc., whose president is a businessman named Fillipo Rovito, Secretary of State records show. While the Rovito family runs the business, the person in charge of the Capri restaurant in Willow Springs goes by the name of ‘Joey Capri.’ He is a member of the Rovito family.

According to Perez, ‘Joey Capri’ told her that he would pay her $75 a day regardless of the number of hours she worked. “The truth is that he never really told me what he was going to pay me until the end of my first work day. He told me that that was what he was going to pay me. I accepted because I take any money I can earn and because I had too many past due accounts,” said the single mother of an 11-year-old girl.

She said her work hours varied, but her shift typically was from 2 pm to midnight on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. On average, she was making about $7.50 per hour. Problems arose quickly when Perez realized that the owner did not pay her what was due and that several checks bounced due to lack of funds. “He always ended up owing me and my sister,” Perez said, who claimed that the same problem was happening to the busboys and cooks, all Hispanic.

When the restaurant closed in March due to the pandemic, Perez was left without a job and $800 in wages. Her sister, Ma Melissa Nieto, who also worked at the restaurant, was owed $250. “‘I’ll pay you tomorrow,’ he would tell me. But he never paid,” she said. “I feel sad because people abuse people like me. They left us without food. I ran out of money for a whole month, and the debt piled up.”

After weeks of trying to recover their wages, the owner finally kicked them out of the restaurant, screaming and threatening to call the police and immigration.

La Raza contacted ‘Joey Capri’ by phone, who denied owing them money and assured that he pays all his employees what they are due and on time. Furious, he told La Raza that he had fired Perez when he discovered that she was not a citizen and that if they continued to contact him, he would call immigration and get her deported [Perez is undocumented]. A day after the phone call with La Raza, the restaurant’s accountant, who refused to confirm her full name, told La Raza that the manager had agreed to pay them. However, according to Sandy Moreno, a worker organizer for Warehouse Workers for Justice, the attorneys representing the sisters will demand a higher sum since the owner also did not pay them the minimum wage.

Perez and his sister received labor rights counseling from Moreno, and the attorneys working in the case are with Raise the Floor Alliance.

Undocumented workers

The fact that a worker is undocumented doesn’t mean that they don’t have labor rights, experts say. “People don’t know it, but all workers have rights because they are workers. If you are a worker, you have labor rights. So people think that because you don’t have [immigration] documents you don’t have rights at work,” Mujica said.

It’s illegal when employers threaten workers with calling immigration. “That is human trafficking. It’s slavery,” Mujica said. “So, education is very important. But it is a daunting task. Some people know it but still don’t ever complain out of fear.”

Mujica commented on a case that occurred a few years ago when a Chinese restaurant chain was taking in workers through a temporary work agency. The chain plotted a scheme where the workers started work on a Monday, and then the next day, the owners would begin provoking fights with the employees. The situation would become unbearable by Wednesday, and when the workers would report to work on Thursday, they would be fired without pay.

“And this was done by several Chinese restaurants on a regular basis every week. All workers were undocumented and mostly Latino. That was detected, reported, and the Illinois Attorney General’s Office and the FBI raided and shut down several of those restaurants,” Mujica said.

“It is important to realize that all workers in this country, regardless of immigration status, are protected by labor and employment laws,” said Dickson, a professor and researcher. “But during the Trump administration, it’s been much harder for many workers, especially undocumented immigrants to enforce their rights because of very real fears of what would happen if they told government authorities about abuses on the job.”

‘Wage theft is done in many ways’

Some companies in industries such as construction, restaurants, car washes, and packing houses, among others, apply cunning tactics not to pay or underpay their workers.

After representing hundreds of workers since 1991, Arise Chicago has determined that there are at least 22 forms of wage theft. Among them: failure to pay full wages (common among construction contractors who promise to pay upon completion of a job and then they disappear); failure to pay time-and-a-half for overtime; payment under the minimum wage; late payment; denying the last check when an employee leaves the company, or the company closes; fining or deducting money from workers for violating any regulation or breaking a product at work; deducting money from workers for company-provided uniforms or company-provided transportation without requesting written permission from the worker; not paying workers for accrued unused vacation; not giving workers all of their tips or forcing them to share them with non-tipped workers; and paying workers with debit cards that charge a fee, among others.

According to experts, a common unlawful labor practice is not paying time-and-a-half for overtime. Maritere Gomez, a campaign labor organizer for Arise Chicago, talked about a case of a young Mexican worker whose job was similar to an auto mechanic. He worked at an auto shop in the suburbs. The young man, whose name cannot be revealed due to a disclosure agreement from a legal settlement between him and the employer, managed to recover nearly $20,000 of unpaid overtime.

“They would ask him to work 12 hours a day with the same pay of $16 per hour. They didn’t pay him time-and-a-half after the 40 hours, something that this workplace didn’t do,” said Gomez. The young man worked there for nearly ten years but only recovered three years of pay because “the law says only three years can be recovered.”

The worker realized the auto shop owed him a large sum of overtime pay when his wife attended a workshop on labor rights presented by Arise. She gave him the information and that’s how he contacted the organization.

Three to four weeks later, the workplace’s attorney and the worker reached an agreement. “Had it been a lawsuit, the law says that the defendant [if they were to lose] would have to pay three times the amount owed to the worker,” Gomez said.

Gomez indicated that the company didn’t maintain records properly and that it didn’t give its employees a paystub with the details of the hours worked and deductions applied, as dictated by law. She believes that’s why they decided to close the case as quickly as possible.

It’s estimated that many workers at that auto shop were also affected by underpaid wages. Still, only this worker sought help.

The eternal dilemma of car washes

“Car washers are terrible places to work. They are very irregular workplaces,” said labor organizer Mujica. “There is a study from 2012, where 56 percent of workers reported wage theft.”

Dickson agreed: “People who work in car washes are already the poorest and the most vulnerable. Those are the worst places to work… and many work under working conditions that are incredibly unsafe.”

An example of a case that ended tragically due to car washers’ unsafe conditions happened in July of 2019 when a Hispanic worker became entangled in a piece of running machinery at Express Car Wash on West Lawrence Avenue in Jefferson Park. After suffering a severe injury, according to Chicago police and the Cook County Medical Examiner, the man was taken to Illinois Masonic Hospital, where he died at 10:46 p.m. The worker, Adam Cerceo, was 45 years old.

Another tragic incident at a carwash took place when a worker was shot and killed by a customer. The disturbance happened in August of 2010 at a Citgo car wash located at 1345 North Pulaski St. when a customer took his Toyota Camry for washing. When a verbal altercation broke out between the client and a worker, who refused to dry his car because the customer was known for not tipping, the client left the compound and then returned and shot dead 43-year-old worker Cesar Rosales.

Although unconfirmed, according to Mujica, the employees claimed that the owner didn’t want to deal with the incident, so he ordered the workers to move Rosales’ body to the sidewalk to make it look like Rosales had been killed in a public area and not inside the establishment.

“The owner said that he wasn’t responsible because technically those weren’t his workers as they were there voluntarily,” Mujica said.

Car washers are also known for worker exploitation. Mujica detailed the case of a car wash called National Carwash located on Broadway Street in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood, which offered car washes for $4, becoming the cheapest place in town for this type of service.

The company used a business model that consisted of hiring homeless. The workers would show up at the location at 6 in the morning and had to pay $12 each day for the opportunity to be “selected” to work there. In addition, workers had to provide their work equipment such as soaps, sprays, and towels.

After a couple complained through Arise, the owners agreed to pay thousands of dollars (the exact amount can’t be disclosed per a legal agreement), Mujica said. The property owners ended up shutting down the business. It’s unknown whether other workers presented similar complaints against this company.

Bureaucracy and lengthy processes: Nearly 80 percent of cases are never solved

A significant challenge that hundreds of thousands of workers face, not only in Chicago but across the country, is the lengthy process they have to go through if their claims are not resolved through nonprofit intermediaries.

When cases end up in public agencies, the process could last two to three years. Some cases have lasted up to eight years to get solved.

There are several ways to present complaints against an employer that’s not abiding by labor rights laws. One way is to submit a complaint through a nonprofit organization specialized in workers’ labor rights. If the employer and the organization reach an agreement, then the case is closed.

But when employers don’t respond, disappear or refuse to pay, then workers can present formal complaints in different jurisdictions and state agencies depending on where the worker resides and the type of complaint.

“Only 20 percent of these cases are settled,” Dickson said. “That’s because for most people it’s their word versus the employer. And the employer has a lot more resources and lawyers to fight them.”

In fiscal 2019-20, the Illinois Department of Labor (IDOL) has received more than 4,500 complaints of wage thefts, mostly for wages, commissions, vacations, and unpaid bonuses. The Department also managed to recover $4.4 million in fiscal 2020 and $3.8 million in fiscal 2019 for unpaid wages.

La Raza contacted IDOL spokesman Michael Matulis, who issued written responses. The statement said the agency doesn’t have the necessary resources to handle all complaints. It also claimed that former Governor Bruce Rauner’s previous administration left a high volume of unprocessed wage claims. For that reason, Governor JB Pritzker and the agency’s director Michael Kleinik “instituted a plan to ensure workers in Illinois are treated fairly.”

Pritzker issued an executive order enforcing that within 60 days, all cases pending under the wage laws that the Rauner Administration accumulated should be reviewed immediately. According to the statement, the department fully complied with the executive order, referring a total of 149 claims involving 13 employers to the Attorney General’s office for action.

Although IDOL has taken several steps to improve its bureaucratic process, the agency recognizes that “in some cases, significant barriers exist in attempts to collect payment from employers. For example, an employer may move to another state that has no reciprocity agreement with Illinois. They may also declare bankruptcy.”

Also, when a decision has been determined, the employer has 35 days to pay or ask the circuit court to review the decision. If the employer doesn’t pay in 35 days or loses in court, then the case is transferred to the attorney general’s office.

In reality, Mujica said, “we’d need an army in charge of this to be expedited.”

Because the processes take so much time, “many people give up or lose interest,” Mujica said, whose organization has recovered more than $8.5 million for workers in the past ten years. “It would take you a lifetime for something to change.”

“Workers also need to know which government agency to turn to. They have to have a level of literacy that’s good enough that they can figure out how to file that complaint. And then they also need to be able to do that without fear of retaliation, which is obviously, very real for many workers, not just undocumented workers,” Dickson said.

In reference to the government’s slowness to resolve these cases, Dickson said she doesn’t believe “that agencies are doing a bad job. I really think it’s a question of resources. Take the car-wash industry, for example, where we know it’s not just a few bad apples, it is almost every single carwash that is doing this. There is no way our State Department of Labor would have the manpower to go out and proactively be tackling an entire industry like this unless they hire hundreds more inspectors.”

Warehouse Workers

Sandy Moreno, a worker organizer for Warehouse Workers for Justice until November 13 and who advised workers Elizabeth Perez and her sister Ma Selissa Nieto, said that another group of workers vulnerable to wage theft are those in the warehouse and packaging industries.

Warehouse Workers for Justice work in collaboration with the Raise the Floor Alliance organization and other legal services in Cook and Will counties.

“We focus on educating the people so that they know their rights,” Moreno said. “I personally have often seen that employers have used COVID-19 as a justification for not paying or underpaying workers after they’ve been laid off. We have seen that employers have tried to use wage reduction, for example, from $11 to like $10 an hour because of COVID-19.”

Moreno, originally from California, said she decided to focus her career on workers’ rights after witnessing her own family of immigrant workers become victims of wage theft. She added: “When I started working at a union in the San Francisco Bay Area, that’s when I started understanding and observing what was happening with workers. I realized that we have rights and that we can do something about it. I feel like it’s my duty to spread the word. There are so many people who need help. They need to know that there are many resources out there.”

Education is the best protection

Labor rights experts unanimously agree that education is the best tool for workers to protect themselves from wage theft. It doesn’t do much good to have new laws if workers aren’t informed.

Unzueta indicated that it is also crucial that workers are organized. “Workers are most vulnerable when they are not organized,” he said, adding that temporary agency workers are one of the most unprotected groups.

“These [temporary] workers are daily-job employees. Technically, the agencies ‘hire’ them every day and then send them to work without guarantees or rights. Workers can’t accumulate vacations nor have health insurance,” Unzueta said. “These agencies are always trying to cheat. There are so many injustices and violations of the law. It’s difficult because many companies are taking advantage of workers’ vulnerabilities as many will do anything for anything so they can maintain their families.”

Unzueta, director of Chicago Community and Worker’s Rights, added that his organization had recovered more than $1.5 million in 2019 for workers. The key to fighting these injustices, he added, “is to always organize, to fight for our rights. We’ve got to fight. We have no choice.”

For information or assistance in labor rights

- Arise Chicago: arisechicago.org, 773-769-6000

- Raise the Floor Alliance: raisetheflooralliance.org, 312-795-9115

- Warehouse Workers for Justice: ww4.org, 815-722-5003

- Chicago Community and Workers’ Rights: chicagoworkersrights.org, 773-653-3664

- S. Department of Labor: www.dol.gov/agencies, 1-866-4-USWAGE (1-866-487-9243)

- Illinois Department of Labor: illinois.gov/, 312-793-2800

—

The production and dissemination of this story has been possible thanks to a grant from the Field Foundation of Illinois through its Media and Storytelling program. La Raza appreciates its support.